Pain is an Electrical Signal Interpreted by the Brain Nerves Bring the Pain Electrical Signal to the Brain

The nerves that bring the pain electrical signal to the brain begin in the various tissues of the body. At the very beginning of the nerve there is a specialized ending call a receptor. The receptor is unique in its ability to initiate the pain electrical signal and send it along the pain nerves (nociceptors) to the brain. The brain interprets the pain electrical signal for a number of parameters (1):

- Location: the region of the body where the pain receptors begin the pain electrical signal to the brain (head, neck, back, finger, toe, etc.).

- Character: whether the pain signal is sharp, dull, aching, burning, stabbing, etc.

The most common cause for the initiation of the pain electrical signal is an inflammatory reaction in the tissues where the pain nerve receptors reside (1).

“The Origin of all Pain is Inflammation and the Inflammatory Response”

It is because of this inflammation-pain response that so much pain is treated with anti-inflammatory approaches:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Omega-3 fatty acids that are found primarily in fish oil

- Ice

- Low-level laser therapy

- Controlled Motion: disperses the accumulation of inflammatory exudates: chiropractic adjusting, massage, passive motions, active motions, etc.

Steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with many side effects, some serious, and some fatal, especially if consumed chronically, including:

- Gastrointestinal bleeding, including fatal bleeding

- End stage renal disease (ESRD)

- Liver damage (hepatotoxicity)

- Heart attacks/strokes

- Dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease

- Hearing loss

- Erectile dysfunction

- Atrial fibrillations

As noted by Giles and Muller (2):

“Adverse reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) medication have been well documented. Gastrointestinal toxicity induced by NSAIDs is one of the most common serious adverse drug events in the industrialized world.”

As noted by Maroon and Bost (3):

“Extreme complications, including gastric ulcers, bleeding, myocardial infarction, and even deaths, are associated with their [NSAIDs] use.”

Almost all patients who take the long-term NSAIDs will have gastric hemorrhage, 50% will have dyspepsia, 8% to 20% will have gastric ulceration, 3% of patients develop serious gastrointestinal side effects, which results in more than 100,000 hospitalizations, an estimated 16,500 deaths, and an annual cost to treat the complications that exceeds 1.5 billion dollars.

“NSAIDs are the most common cause of drug-related morbidity and mortality reported to the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world.”

One author referred to the “chronic systemic use of NSAIDs as ‘carpet-bombing,’ with attendant collateral end-stage damage to human organs.”

Chiropractic spinal adjusting reduces pain by using mechanisms that function in addition to the ability to help disperse the accumulation of inflammatory exudates. The most noted of these applies to the mechanical “closing of the ‘Pain Gate’” (4, 5, 6).

•••••

Whatever Tissue is Causing Spinal Pain, it Must Have a Nerve Supply

It has been understood for decades that the articular hyaline cartilage has no nerve supply, and consequently is not capable of initiating the pain electrical signal. This holds true, even when the cartilage is injured. Sadly, injured articular hyaline cartilage degenerates at an accelerated rate (7, 8, 9, 10), creating arthritic changes that often irritate and inflame adjacent tissues, eventually generating the pain electrical signal to the brain. This is the explanation as to why some spinal injuries are initially asymptomatic, but become painful as a function of time as the degenerative process progresses.

Other tissues that have been shown to be pain insensitive include the fascia (11).

Stephen Kuslich and colleagues completed an extensive assessment, involving 700 live humans, as to the tissue sources of spinal pain in 1991 (11). These authors performed 700 lumbar spine operations using only local anesthesia to determine the tissue origin of back pain. The tissues they assessed for pain generation included skin, fat, fascia, supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, spinous process, muscle, lamina, facet capsule, facet synovium, nerve root, dura, compressed nerve root, normal nerve root, annulus fibrosus of the disc, nucleus of the disc, and vertebral end plate. All of these tissues, except for the fascia, were capable of producing spinal pain. They discovered that the primary “sight” for chronic back pain was the annulus of the intervertebral disc.

Pertaining to the cervical spine, studies have indicated that the primary tissue that initiates the chronic neck pain signal is the facet joint capsular ligaments (12, 13).

Interim Summary

Spinal pain is an electrical signal in the brain. The pain electrical signal is brought to the brain by pain nerves (nociceptive). The pain nerves have receptors that initiate the pain electrical signal, and these receptors exist in most spinal tissues, but the most clinically relevant are in the intervertebral disc and in the facet joint capsular ligaments. The primary “trigger” for the initiation of the pain electrical signal from these tissues is inflammation and the inflammatory response.

The inflammatory response that initiates the pain electrical signal can have a number of causes, including:

- Infection

- Autoimmune disease

- Injury (trauma)

- Chronic mechanical stress

The healthcare provider attempts a differential diagnosis between these different etiologies by assessing factors such as history, family history, systemic factors, etc. The healthcare provider may also rely upon imaging and laboratory findings. Each of these can be influenced by individual genetics, epigenetics, nutrition, prior life events (injuries, pregnancies, etc.), occupation, ergonomics, age, fitness, etc. Successful management depends upon ascertaining a clear (or reasonably probable or suspected) etiology. A prudent healthcare provider will consequently do their best to make an accurate differential diagnosis.

•••••

Chiropractic clinical practice specializes in injury (trauma) and/or chronic mechanical stress as the etiology. Chiropractors not only treat the mechanical findings, they also inform the patient as to causation and to continuing causes of their ongoing mechanical problems that are initiating their pain. The chiropractor then coaches the patient on strategies to avoid or minimize the mechanical causes of their tissue inflammatory response. Often, patients can prevent future spinal problems by using this same practical advice. The basic advice requires knowledge of levers.

The efficiency of human function in a gravity environment is an integration of mechanics and biology, known as biomechanics. Mechanics comprises a group of simple machines, which include:

- Lever

- Pulley

- Screw

- Wedge

- Inclined plane

- Wheel and axle

The most important of these simple machines as applied to human upright posture and spinal syndromes is the lever. Levers allow for increased efficiency of strength and movement. The increased efficiency of the lever is called mechanical advantage.

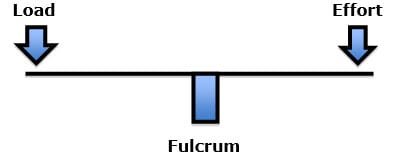

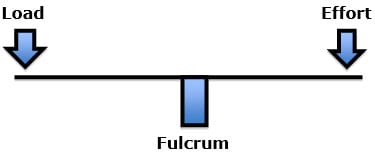

There are three classes of levers. All three types of levers have three common features:

- Fulcrum (the pivot point)

- Load (resistance, weight)

- Effort (applied force)

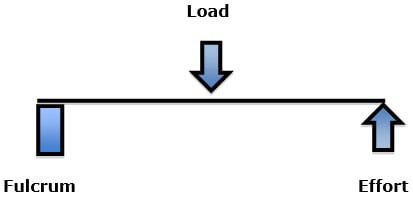

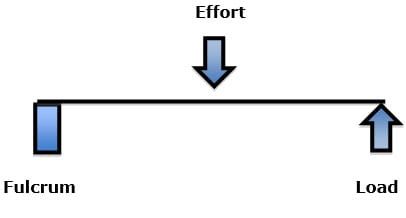

It is the sequential arrangement of the three common features that determine the class of the lever:

First Class Lever: load fulcrum effort

Examples of a first-class lever include a teeter-totter or crowbar.

Second Class Lever: fulcrum load effort

An example of a second-class lever is a wheelbarrow: The wheel is the fulcrum; the effort is the handlebars; the load is in between.

Third Class Lever: fulcrum effort load

An example of a third-class lever is tweezers, where the effort is applied between the fulcrum and the load.

•••••

The strongest mechanical structure is a column. This is why engineers use columns to support bridges and buildings. However, the human spine cannot function as a column. The human spine must be able to allow us to bend, stoop, lift, twist, etc. Consequently, a different mechanical design is required. Upright human posture is a three dimensional first class lever mechanical system, such as a teeter-totter or seesaw (14, 15).

Recall, in the first class lever, the fulcrum is located between the load and the effort.

The fulcrum of a first class lever is the place where the load is the greatest: if excessively heavy objects are placed on both ends of the teeter-totter, it will break in the middle, at the fulcrum.

The force experienced at the fulcrum of a first class lever system is dependent upon three factors:

The magnitude of the load (weight)

The distance the load is away from the fulcrum (lever arm)

The addition of the counterbalancing effort required to remain balanced

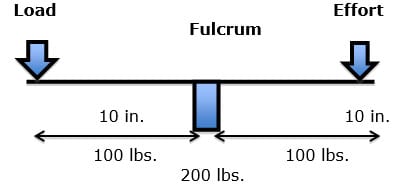

If the load was 10 lbs., and the distance from the fulcrum was 10 inches (the lever arm), the force on the fulcrum would be 100 lbs. (10 X 10). In order to remain balanced, the effort on the opposite side of the fulcrum would have to also be 100 lbs. The effective load applied to the fulcrum would be 200 lbs. Thus an actual load of 10 lbs. would have an effective load on the fulcrum of 200 lbs.

The effective load (EF) at the fulcrum is the actual load (AL), multiplied by the lever arm (LA), plus the counterbalancing effort (CBE):

EL = 10 lbs. (AL) X 10 in. (LA) + 100 lbs. (CBE) = 200 lbs. (EL)

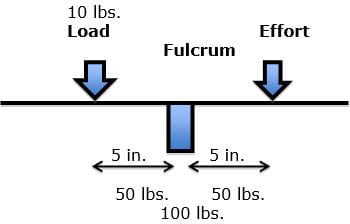

If the same actual load were closer to the fulcrum, the effective load changes significantly:

EL = 10 lbs. (AL) X 5 in. (LA) + 50 lbs. (CBE) = 100 lbs. (EL)

•••••

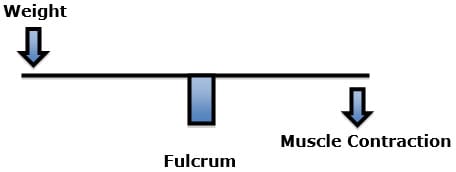

In the spine, the fulcrum of the first class lever of upright posture is primarily the vertebral body/disc, and the two facet joints.

The actual load includes the weight of our own body and the weight of anything we are lifting or carrying.

The effective load is the actual load multiplied by the length of the lever arm between the actual load and the fulcrum (disc and facets).

The effort is the required contraction of the spinal muscles, on the opposite side of the fulcrum, to keep the spine balanced and prevent it from tipping over. This muscle contraction adds to the load at the fulcrum.

This means that when the first class lever of upright posture is altered, for any reason, there is an increased effective mechanical load born by the fulcrum, i.e. the spinal intervertebral discs and facet joints. Such increased mechanical loads accelerate degenerative joint disease and the inflammation, altering the pain thresholds (14, 16). In their 1990 book Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine (15), White and Panjabi state:

“The load on the discs is a combined result of the object weight, the upper body weight, the back muscle forces, and their respective lever arms to the disc center.”

Events that increase the actual load at the spinal joints (disc and facets and require counterbalancing muscle contraction include postural distortions, lifting ergonomics (14), and weight problems (15).

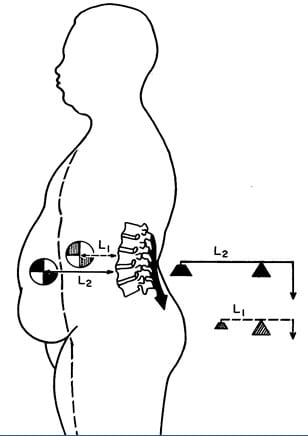

When a person gains abdominal weight (obesity, pregnancy), the first class lever system of upright posture is altered in such a manner that the intervertebral disc and facet joints bear significantly more weight. To counterbalance the weight, the muscles on the other side of the fulcrum (spine) must constantly contract with more force, or the person would fall forward. The black arrow attached to the posterior spinal elements represents the muscle contraction (14).

This constant muscle contraction with more effort, creates muscle fatigue and myofascial pain syndromes. Rene Cailliet, MD states “This increase [in muscle tension] not only is fatiguing, but acts as a compressive force on the soft tissues, including the disk.” (14).

•••••

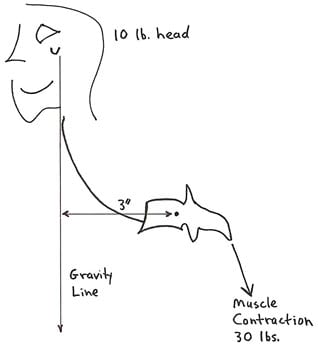

Rene Cailliet, MD, also uses the first class lever example in his 1996 book Soft Tissue Pain and Disability pertaining to the forward head syndrome (17). The patient has an unbalanced forward head posture. Dr. Cailliet assigns the head a weight of 10 lbs. and displaces the head’s center of gravity forward by 3 inches. The required counter balancing muscle contraction on the opposite side of the fulcrum (the vertebrae) would be 30 lbs. (10 lbs. X 3 inches):

The constant muscle contraction required to balance postural distortions creates muscle fatigue and myofascial pain syndromes.

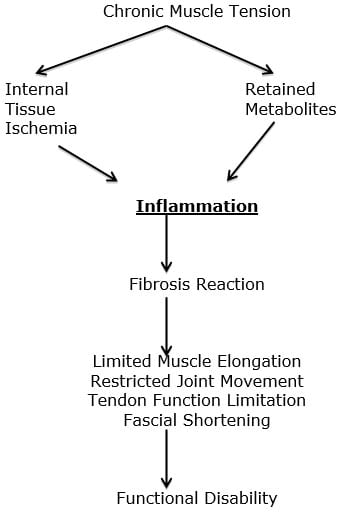

Dr. Cailliet explains how the constant contraction in the counterbalancing muscles creates a cascade that leads to muscle fatigue, inflammation, fibrosis, and eventually to chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes (17):

It is the increased effective loads at the spinal discs and facet joints (the spinal fulcrum) that accelerate degeneration and inflammation and are of particular concern in spinal pain syndromes. One should not discount the contribution of inflammation and pain from the contraction of the counterbalancing muscles and myofascial pain syndromes.

SUMMARY

It is much easier to hold a 10 lb. weight against your chest than in an outstretched arm. The reason is leverage. With the first class lever of upright posture, the most vulnerable tissues to mechanical loading stress, breakdown, degeneration, inflammation, and pain are the intervertebral disc and facet joints. This is because they function as the fulcrum. Numerous studies have identified the intervertebral disc and facet joints as the primary generators of chronic spinal pain. Likewise, the leverage stress applied to the fulcrum (disc and facets) must be counterbalanced my muscle contraction (effort), or the patient would fall over. This leads to chronic muscle problems (myofascial pain syndrome).

Practical Advice

- Weight: Excess body weight increases the weight to the disc and facet joints (the fulcrum). Increased weight increases compression, degeneration, inflammation, and pain. Also, excess weight is not gained symmetrically. The rule is most weight gain is at the abdomen. This creates a lever arm that multiplies the actual load (weight) to a significantly higher effective load on the fulcrum (disc and facets). The back muscles must then contract to maintain upright posture, further adding to the effective load (weight) to the spinal joints.

- Posture: Poor posture significantly increases the effective load to the spinal joints and triggers counterbalancing muscle contraction (effort). An easily understood example is the forward head of Cailliet above. Poor spinal posture is routinely addressed by chiropractors.

- Ergonomics: Individuals with acceptable posture may assume unacceptable postures during required work or leisure activities. Such activities may include “sitting at desk” postures, or “driving a vehicle” postures. During all such activities, the more one is coached to keep the center of masses of the parts of the body in alignment, the smaller the lever arm stress to the joints, and the less counterbalancing muscle contraction required (effort). Chiropractors routinely coach patients on such ergonomic issues.

Poor posture significantly increases the effective load to the spinal joints and triggering counterbalancing muscle contraction (effort).

- Bending: Bending forward at the waist to pick up an object, even a light object like a shoe or sock or pencil on the floor, can create significant adverse mechanical loads at the spinal disc and facets (the fulcrum). It is not the weight of the object, but rather it is the weight of the body multiplied by the lever arm, and also the required muscle contraction to become upright again. Bending is always risky for the spine. Stooping with the legs is always preferred when possible.

- Lifting: Lifting by bending is the same as bending (above) with the addition of the weight of the object being lifted. This is well illustrated by White and Panjabi above.

REFERENCES

- Omoigui S; The biochemical origin of pain: The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007, Vol. 69, pp. 1169 – 1178.

- Giles LGF; Muller M; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine July 15, 2003; 28(14):1490-1502.

- Maroon JC, Jeffrey W. Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain; Surgical Neurology; 65 (April 2006) 326–331.

- Melzack R, Wall PD; On the nature of cutaneous sensory mechanisms; Brain; 1962 Jun;85:331-56.

- Melzack R, Wall PD; Pain mechanisms: a new theory; Science. 1965 Nov 19;150(3699):971-9.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985, Vol. 31, pp. 535-540.

- Hadley Lee; Anatomical Roentgenographic Studies of the Spine, Thomas; 1972.

- Jackson R; The Cervical Syndrome; Thomas; 1978.

- Ruch W; Atlas of Common Subluxations of the Human Spine and Pelvis; CRC Press, 1997.

- Gargan MR, Bannister GC; The compararive effects of whiplash injuries; The Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine; 19(1), 1997, pp. 15-17.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America, Vol. 22, No. 2, April 1991, pp.181-7.

- Bogduk N, Aprill C; On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks; Pain; August 1993;54(2):213-7.

- Bogduk N; On Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Pain After Whiplash; Spine; December 1, 2011; Volume 36, Number 25S, pp S194–S199.

- Cailliet R; Low Back Pain Syndrome, 4th edition, F A Davis Company, 1981.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, Second Edition, Lippincott, 1990.

- Garstang SV, Stitik SP; Osteoarthritis; Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Pathophysiology; American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; November 2006, Vol. 85, No. 11, pp. S2-S11.

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; F A Davis Company, 1996.